Your cart is empty now.

Jehovah Afflicted In All Our Affliction

“In all their affliction he was afflicted, and the angel of his presence saved them: in his love and in his pity he redeemed them; and he bare them, and carried them all the days of old” (Isaiah 63:9).

Introduction

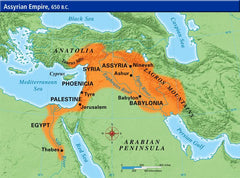

Isaiah wrote to God’s people Israel when they were in great need of comfort from heaven. When Isaiah prophesied, Israel (or, at least, Judah) was still a nation, but their future was very bleak. It would take several generations, but eventually Israel would go into captivity. Isaiah writes from the perspective as if Israel were already in captivity. He prophesies their exile to Babylon as well as their return from Babylon some seventy years later, but he himself lived several generations before the captivity, mostly during the reign of king Hezekiah of Judah.

The Babylonian Captivity, which from Isaiah’s perspective was coming, and because of God’s eternal decree was certain, would be very traumatic for Israel. That trauma is evident in the books of Ezekiel and Daniel, for example. Israel would be tempted to despair: has God forgotten his people and his promises? In Babylon Israel would ask, “Does God care about us as we languish here?” And the answer of Isaiah to them and to us is this: God cares more than we could ever know.

PITYING US

If Jehovah is afflicted in all our affliction, that means that he pities us. In verse 9 two of God’s attributes are mentioned: love and pity. “In his love and in his pity he redeemed them” (v. 9).

The Hebrew verb for “love” is very expressive. It means to breathe after or to pant for someone. The word “love” is not used in Psalm 42:1, but the idea is there: “As the hart panteth after the water brooks, so panteth my soul after thee, O God.” Visualize in your mind a deer longing for, panting after, breathing after water. Perhaps the deer has been pursued by a wolf or a hunter and it is exhausted from running and is now parched with thirst. Then imagine the Psalmist so longing for Jehovah his God. That longing is an expression of love: to breathe after someone in affection.

Flowing from that panting are two other aspects of love, namely: the desire or determination to do good to the person whom one loves; and the desire or determination to draw near to that person in fellowship so that one creates a bond with that person whom one loves.

With that kind of love Jehovah loves his people: Jehovah breathes after us or pants after us in deep, ardent affection. Jehovah determines to do us good, the greatest good, which is salvation. Jehovah draws near us and establishes his covenant with us. Jehovah will not be satisfied until we are safely with him in heaven forever.

Jehovah says so in many places of his Word, lest we ever forget it. In Deuteronomy 7:7 God declares: “The LORD did not set his love upon you, nor choose you, because ye were more than number than any people; for ye were the fewest of all people, but because the Lord loved you, and because he would keep the oath.” In Jeremiah 31:3 the prophet declares in the name of God: “The Lord hath appeared of old unto me, saying, Yea, I have loved thee with an everlasting love: therefore with lovingkindness have I drawn thee.” That’s love: Jehovah’s breathing after us in affection; Jehovah’s determination to do good to us; and Jehovah’s drawing near to us to bless us in his covenant. “In his love and in his pity he redeemed them,” we read in verse 9.

In addition, there is the second word, “pity.” … “in his pity he redeemed them.” The Hebrew word for “pity” in verse 9 is quite rare. It comes from a root which means “to spare.” It has the idea of refraining from inflicting misery, hurt, or harm on someone. More generally, the word “pity” is another word for “mercy.” In verse 7 the prophet uses a number of more common words for mercy: “I will mention the lovingkindnesses of the Lord and “mercies” and “goodness.”

Mercy is Jehovah’s compassion on the miserable. “M” is for misery and “M” is also for mercy: Jehovah’s mercy has various aspects also. We can identify at least three components/aspects to God’s mercy: first, God sees and takes note of our misery; second, God desires or determines to deliver us from our misery; and third, God powerfully delivers us from our misery.

The result of God’s mercy/pity is that he makes us perfectly and everlastingly blessed. Or the result is that he delivers us from the deepest misery of our sin and death and brings us into the greatest blessedness of everlasting life.

All of those components are displayed in divine mercy, in Jehovah’s mercy. If one of these components is missing, there is no real mercy.

A god who does not see or take note of our misery is not merciful. A god who sees, but does not will to deliver us from misery, is not merciful. A god who sees and wills, but does not act to deliver us, is not merciful either. If Jehovah does not deliver his people, he is either powerless or cruel.

But Jehovah is neither powerless nor cruel. We confess in the Heidelberg Catechism LD 9: “He will make whatever evils he sends upon me, in this valley of tears, turn out to my advantage, for he is able to do it, being Almighty God, and willing, being a faithful Father” (A 26). We also confess in Belgic Confession, Art. 13, “He watches over us with a paternal care” and in the Baptism Form: “He will avert all evil or turn it to our profit.”

Love and pity, especially pity, are necessary especially when we are afflicted. That is the context: Isaiah describes affliction: “in all their affliction.” The reference is to Israel’s affliction: in verse 7 we read, “I will mention… the great goodness toward the house of Israel, which he hath bestowed upon them according to his mercies and according to the multitude of his lovingkindnesses.” Then Jehovah says, “Surely, they are my people” (v. 8).

Let us understand what affliction is.

Affliction is any circumstance of life that brings distress or anguish. The Hebrew word rendered “affliction” has the idea of being restricted, cramped, or pressed down. In the Bible if someone is afflicted, he is in desperate straits, in a narrow place, hard-pressed, or stressed. For Israel the great affliction that Isaiah has in mind was yet to come. It was the looming Babylonian Captivity, the invasion of the Promised Land by heathen armies, the cutting off of the throne of David, the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple, and the carrying away of Israel into exile.

In addition, the text looks backward: Not “in all their affliction he will be afflicted, although that is true, but “In all their affliction he was afflicted:” Israel had a long history of affliction. Chief among her afflictions was the bondage in Egypt under which Israel had suffered for some 400 years.

Affliction for us includes many things that affect us in our lives. Affliction can affect the body or the mind (or the soul) and often both. We might have severe pain in our body caused by a disease; we might suffer from severe depression or anxiety caused by trauma; we might be mocked, neglected, rejected, or persecuted; there might be trouble in our family, at work, at school, or in the church; or we might be laboring under a heavy burden of guilt or struggling with a powerful temptation. Those are afflictions.

And our temptation in affliction is to think, “God does not know my affliction; and, if he does know, he does not care; and if he does care, he is powerless to help me in my affliction.” That was Israel’s temptation as she looked with dread to the Babylonian Captivity. That might be our temptation as we look to the future, to the trials that we already experience or fear to go through in the future.

AFFLICTED WITH US

Isaiah had a word from Jehovah to his afflicted people, and he has a word from Jehovah to us: “in all their [Israel’s] affliction he [Jehovah] was afflicted” (v. 9).

Before we try to understand that Word of God, let us understand its importance for Israel. Israel would come to a point where she feared that God was no longer merciful. There are times when God’s people think in that way—in that wrong way. We see that sometimes in the Psalms. In Psalm 77 Asaph cried, “Will the Lord cast off forever? And will he be favourable no more? Is his mercy clean gone forever? doth his promise fail for evermore? Hath God forgotten to be gracious? hath he in anger shut up his tender mercies?” (Ps. 77:7-9). Or we find that sentiment in this chapter: “Look down from heaven, and behold from the habitation of thy holiness and of thy glory: where is thy zeal and thy strength, the sounding of thy bowels and of thy mercies toward me? are they restrained?” (v. 15).

Israel would react in that way because of the Babylonian Captivity: it appeared that God took no notice of their misery, that God did not desire to deliver them from their misery, or even that God could not deliver them from their misery.

That is sometimes also the case with us; we begin to think gloomy thoughts in our misery. Does God not notice I am sick? I am suffering a crippling and painful disease. Does God not know that I am reeling because of an unexpected diagnosis.? Does God not care that my loved one is sick or even dying? Does God not care about my grief, my anxiety, or my depression? Does God not see that I am in great need? Does God not care that I have great disappointment in my life, that I am struggling at school or at work?

But so far is it from being true that Jehovah does not care that Isaiah says, “In all their [Israel’s] affliction, he [Jehovah] was afflicted” (v. 9). Or we could say today, “In all their [the church’s and every individual Christian’s] affliction he [our heavenly Father] was afflicted.”

That is, in fact, a startling word of God—if it was not written in black and white on the page of Scripture, we would hardly dare say it. As it were, Jehovah, when he saw the affliction of Israel, was anguished. As it were, Jehovah, when he saw the affliction of Israel, was restricted, cramped, or pressed down. As it were, Jehovah, seeing the affliction of Israel, was in desperate straits, in a narrow place, hard-pressed, or stressed. But more than that, Jehovah did not merely see it: Jehovah was in it.

Of course, we have to be careful to understand that in light of who Jehovah is. The text is speaking here of Jehovah—not a human being, but Almighty God. We may not interpret this by making it clash with God’s omnipotence, God’s sovereignty, or God’s unchanging blessedness, but we also may not explain it away, so that it has no real meaning—that, too, is the temptation that we face.

This truth is taught not only here, but it is revealed elsewhere in Scripture. Two incidents in Israel’s history in particular stand out. The first is before the Exodus from Egypt and the second is after that Exodus. We read in Exodus 2:23: “The children of Israel sighed by reason of the bondage, and they cried, and their cry came up unto God by reason of the bondage. And God heard their groaning, and God remembered his covenant with Abraham, with Isaac, and with Jacob. And God looked upon the children of Israel, and God had respect unto them [or God knew them]” (Ex. 2:23-25).

Jehovah did not look down upon his people in cold indifference: he saw what the Egyptians were doing; he heard the cries of his people; and he remembered his covenant. In a similar way, our heavenly Father sees every tear that we shed in pain and sorrow; he knows every anguished thought of our hearts and minds; he knows everything that others do to oppress us in body or soul; and at the time appointed he delivers us, either by removing the affliction, or by giving us grace to bear it, or by using it for our good.

We also read in Judges 10:16: “And they put away the strange gods from among them, and served the Lord: and his soul was grieved for the misery of Israel.” The misery caused by the Philistines and the Ammonites moved Jehovah to pity them so that he sent Jephthah, the judge, to deliver them.

God being afflicted in all our affliction includes a number of important truths: first, God is not indifferent to our affliction; he is not aloof, distant, and unfeeling, but he knows and he cares. It means, second, that God sympathizes with us in our affliction. It means, third, that God’s heart goes out to us when we are afflicted, so that he wills to spare us and to bless us; and it means, fourth, that when his purpose with our present affliction is complete, he will stretch out his mighty arm to deliver us from it.

With those truths in mind, we must not misunderstand the prophet in a way dishonoring to God.

Recall three things we know about God from his name Jehovah. First, Jehovah is eternal—can the eternal God be afflicted? Second, Jehovah is unchangeable—can the unchangeable God be afflicted? Third, Jehovah is independent or self-sufficient—can such a God be afflicted?

Consider especially God’s unchangeability and self-sufficiency. Affliction means change. Affliction changes our condition from blessedness to misery; affliction leads to an emotional reaction, but God is unchangeable: he cannot change from blessed to miserable and back to blessed. Affliction also means that something outside of us can affect us, can have a negative effect upon us: nothing outside of God can have a negative effect upon him so as to make him miserable: if he could, it would have to be removed for God to enjoy blessedness. Then God would not be independent. And if Jehovah were neither unchangeable nor independent, he would not be God. How, then, can God be afflicted; and how can Isaiah say about Jehovah, “In all their affliction he was afflicted”?

We have already identified four things, but we can expand the explanation. The four things were these. First, God is not indifferent to our affliction, for he knows and cares; Second, God sympathizes with us; Third, God’s heart goes out to us; and fourth, God will stretch out his mighty arm to deliver us from it.

More than that: it means that God so identifies with us that our sorrows become his sorrows; our pains become his pains; and our afflictions become his afflictions. Although he does not personally feel those afflictions, he loves us who do feel them, and his heart goes out to us as a father’s heart goes out to his hurting child. “Like as a father pitieth his children, so the Lord pitieth them that fear him” (Ps. 103:13).

This is because of sovereign, unconditional election. In eternity God made himself one with us, so that he now and forever binds himself to us. In eternity God gave us to his Son, so that he might in time and history save us from our sins and miseries. Therefore, our cause is his cause; or, better, his cause is our cause. Our joys are his joys; and our sorrows and afflictions are his sorrows and afflictions.

Thus the Bible says in 1 Peter 5:7, “Casting all your care upon him, for he careth for you.” That simply means this, “You matter to him.” Your cries of anguish matter to him; in those days when you feel overwhelmed you matter to him; your secret tears matter to him. They might not matter to others, but they matter to him. “Thou tellest my wanderings: put thou my tears into thy bottle: are they not in thy book?” (Ps. 56:8).

Ultimately, Jehovah is afflicted in our afflictions in Jesus Christ. Isaiah 63:9 is the Old Testament equivalent, or shadow, of Hebrews 4:15. What could not really or properly be true of Jehovah, that is, that he was afflicted, is true of Jesus Christ, Jehovah in the flesh. “For we have not an high priest which cannot be touched with the feeling of our infirmities, but was in all points tempted like as we are, yet without sin” (Heb. 4:15).

Jesus, the Son of God, knows what affliction is: he knows what it is to be crushed in body/soul; he knows what it is to suffer pain and agony; he knows what exhaustion, hunger, and thirst are; and he knows what sorrow of the soul is. Therefore, we, more so even than Israel did, have in heaven one who understands us, who has deep sympathy for us, one afflicted in our affliction.

SAVING US

Jehovah’s love and pity do not end in inaction: we read, “he saved them.” Specifically, “The angel of his presence saved them” (v. 9). Literally, the angel of his presence is the angel of his face. The face of Jehovah shows us his demeanor, disposition, or attitude displayed toward us. Jehovah’s face is against the wicked, but when we look into Jehovah’s face in faith we see love and pity: we see affection, sympathy and compassion.

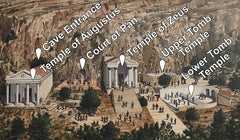

The angel of Jehovah’s presence is not a created angel like Gabriel: Jehovah has created many such angels, but none of them is the angel of Jehovah’s presence. Rather, the angel of Jehovah’s presence (or face) is fully divine: Jehovah himself. The name for “the angel of Jehovah’s presence” is simply the angel of the LORD. That angel, an uncreated messenger of Jehovah, appears at many crucial points in Old Testament history: for example, he stops Abraham from killing Isaac in Genesis 22; he appears to Moses in the burning bush in Exodus 3; he withstands the false prophet Baalam in Numbers 22; he appears multiple times in the book of Judges; he refreshes Elijah in 1 Kings 19; and he slays the Assyrians in 2 Kings 19. In those passages it is very clear that the angel of Jehovah (the angel of his presence or face) is none other than Jehovah himself—the pre-incarnate Son of God.

This angel, we read, in the text, saved Israel; and Jesus Christ saves us. In his love and pity, and as he makes our affliction his own, he acts in mighty power.

Three things he does for us according to Isaiah 63:9. First, he saved Israel (and he saves us): he delivers us from sin and death and brings us into the possession of everlasting life. Second, he redeemed Israel (and he redeems us). Redemption is a specific kind of salvation: it is salvation from bondage, slavery, or imprisonment by means of the payment of a price. In the Old Testament Jehovah redeemed Israel from Egypt, and he would also redeem Israel from Babylon; in the New Testament Jesus Christ redeemed us with his own blood. By shedding his blood on the cross he redeemed us not only from the penalty and punishment of sin, which is death, but also from the power and bondage of sin. Third, he bare (bore) and carried Israel, that is, he directed them, guided them, and even brought them through the wilderness into the Promised Land of Canaan, and he would carry that out of Babylon too (and he bears and carries us through this life to heaven).

Let that be our comfort as we face an uncertain future. With all of its uncertainties, its joys, its sorrows, and its afflictions. In all our affliction Jehovah God (in Jesus Christ) is afflicted. He cares for us; he loves us; he pities us; and he will surely save us, redeem us, and even carry us.

God is not indifferent to our affliction, for he knows and cares; God sympathizes with us; God’s heart goes out to us; and God will stretch out his mighty arm to deliver us from all evil.

__________

Martyn McGeown is a pastor in the Protestant Reformed Churches. He is also the editor of the RFPA blog and the author of multiple RFPA publications. Read more of his work by clicking this link or the image below.

The content of the article above is the sole responsibility of the article author. This article does not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of the Reformed Free Publishing staff or Association, and the article author does not speak for the RFPA.

Donate

Your contributions make it possible for us to reach Christians in more markets and more lands around the world than ever before.

Select Frequency

Enter Amount