Your cart is empty now.

The Nicene Creed

This article was written by Rev. James Slopsema and published in the October 1, 1982 issue of the Standard Bearer.

_____________

An overture appeared at our last Synod that there be included in our Psalter "the three early-church Trinitarian Creeds: the Apostles' Creed, the Nicene Creed, the Athanasian Creed; with a brief historical introduction to each creed." The first and chief ground of the overture was that although we do receive these creeds according to Article 9 of the Belgic Confession, yet the Nicene and Athanasian Creeds are not easily accessible to our people and are thus also unfamiliar.

This overture was not treated at our last Synod because it did not come to the floor of Synod in the proper way. Whether it will appear at our next Synod remains to be seen. This overture shows a concern that the Nicene and Athanasian Creeds be better understood by our people and be more used by them, even as is the Apostles' Creed. This is certainly a legitimate concern. If we receive these three creeds as we acknowledge in the Belgic Confession, then we certainly ought to be familiar with them and use them. With the Apostles' Creed we are quite familiar. It is recited every Sunday in our worship service. It is incorporated in our Heidelberg Catechism and explained. We also find it in our Lord's Supper form. But concerning the Nicene and Athanasian Creeds we probably know very little. Perhaps we have never even read them. It is with a view to correcting this situation that we make a study of the Nicene Creed. Our purpose is to become more familiar with this creed that we may truly receive it as we confess.

The Nicene Creed is as follows:

I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds; God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God; begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father, by Whom all things were made.

Who, for us men for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Spirit of the virgin Mary, and was made Man; and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate; He suffered and was buried; and the third day He rose again, according to the Scriptures; and ascended into heaven, and sitteth on the right hand of the Father; and He shall come again, with glory, to judge the quick and the dead; Whose kingdom shall have no end.

And I believe in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver of Life; Who proceedeth from the Father and the Son; Who with the Father and Son together is worshipped and glorified; Who spake by the prophets.

And I believe one holy catholic and apostolic Church. I acknowledge one baptism for the remission of sins; and I look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

Before we turn our attention exclusively to the Nicene Creed we ought perhaps to say several things yet about the Apostles', Nicene, and Athanasian Creeds in general.

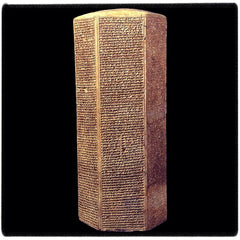

These three creeds were formulated by the church in her early history. The Nicene Creed was formulated at the great council of Nicea (325 AD) with minor changes being made at subsequent church councils. The Apostles' Creed, you will notice, is quite similar to the Nicene Creed. The Apostles' Creed was not formulated by the twelve apostles, as the name may seem to suggest. It was formulated by the early Christian church as she sought to give expression to the teachings of the apostles. This creed was not formulated by any particular council of the church. It arose gradually in the western branch of the church (Italy and North Africa), whereas the Nicene Creed was most popular in the eastern branch of the church. The Apostles' Creed, as we have it in our present day form, appeared about the beginning of the sixth century. The Athanasian Creed, as the name indicates, has often been attributed to the great church father Athanasius. It is however quite certain that Athanasius is not the author of this particular creed. It too, like the Apostles' Creed, simply arose from within the church and dates from the beginning of the ninth century.

These three creeds are commonly called the Ecumenical or General Creeds of the church. This name indicates that these creeds are honored and maintained by all of Christendom. They are the property of the Christian church in general. All that goes by the name of Christian adheres to these creeds. The reason for this is simple. These three creeds set forth the basic principles and tenets of the Christian faith. They contain the truth of God's Word in its most simplified form.

Of the three Ecumenical creeds the Nicene and Apostles' Creeds are the most popular and widely used today. The Reformed churches have historically made use of the Apostles' Creed. As we pointed out earlier, the Apostles' Creed is incorporated and explained in the Heidelberg Catechism; it is included in the Lord's Supper form; and it is used in the liturgy of our worship service. The Nicene Creed is also used similarly by other churches. Thus, for example, it has been incorporated and expounded in all the orthodox Greek and Russian catechisms. It is also used liturgically by the Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran churches.

That brings us to the question of the status of the Ecumenical creeds. According to Article 9 of the Belgic Confession we "receive" these three creeds. When we receive a creed we first recognize that it faithfully sets forth the truth of God's word. This is in harmony with the true nature of creeds. The nature or purpose of a creed is to set forth in summary form the truth of scripture. Scripture is the sole rule of doctrine and life; it is the only standard of faith. In her creeds, however, the church seeks to summarize that which she finds in the scriptures. To receive a creed therefore implies a recognition that a particular creed is such a faithful summary of scripture. But, secondly, to receive a creed also means that we believe with our heart and confess with our mouth all that is contained within that creed. This all holds true with respect to the Ecumenical creeds which we according to the Belgic Confession receive.

The Ecumenical creeds are related to our own three forms of unity. That we receive the three Ecumenical creeds may seem to suggest that these are simply three more creeds which we have in addition to our Heidelberg Catechism, Belgic Confession, and Canons of Dordt. In that case we would have six creeds instead of three as the confessional basis of our church. Such, however, is not the case. The Ecumenical creeds which we receive are not additions to our three forms of unity; they are rather the root from which our three forms of unity have grown and developed.

In the age in which they were formulated, the three Ecumenical creeds were more than sufficient to express the faith of the church. These creeds grew out of the great Trinitarian and Christological controversies of the early church in which all the important truths of the Trinity and the deity of Christ were called into question. In response to the errors that arose during the course of these controversies, these three creeds were composed. In them the church set forth very succinctly and beautifully the truth of God into which she had been led. In their own day these creeds were more than adequate to express the faith of the church and to defend that faith over against the heresy of the day.

But nothing stands still in history. Heresy and false doctrine do not. There is a continual growth and development of these as the powers of darkness seek to destroy the church. This in turn gives impetus to the development of the truth. The truth of God is not developed by the church in a vacuum or in some ivory tower. The truth is developed only in response to the rise of false doctrine as the church strives to maintain the truth over against that false doctrine. But as the church over the course of the ages develops the truth of the scripture over against the lie of unbelief, she finds that she needs new confessions. Certainly the old confessions are faithful and true. But the old confessions are no longer adequate to express the truth of God as the church has been led to develop it. Neither are the old confessions adequate to defend the truth of God over against the lies of unbelief which also have grown and developed. There is a need for a new confession built upon the old in which the church expresses the fullness of the truth as she has been led to see and develop it. She needs new confessions in which the old confessions are further elaborated upon and developed in harmony with the development that has taken place in the church.

This is exactly what happened to the three Ecumenical creeds. Much has happened since the time of their formulation. The lie has developed considerably since the period of the early Christian church and so too has the truth. The creeds of the ancient church are no longer adequate for today. There came a time when new, more elaborate creeds had to be formulated. These new creeds arose primarily during the great Protestant reformation of the 16th and 17th centuries. These new creeds were based on the old ecumenical creeds and further elaborations of them. The new creeds which arose in the Reformed branch of the reformation were our three forms of unity: the Heidelberg Catechism, the Belgic Confession, and the Canons of Dordt.

Herein we see the value of the old Ecumenical creeds. The Ecumenical creeds are the basis and root out of which developed the creeds which we hold so dear today and use as the confessional standard of our churches. Certainly then we receive these ancient creeds of the church. And they are certainly worthy of our study and consideration.

The content of the article above is the sole responsibility of the article author. This article does not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of the Reformed Free Publishing staff or Association, and the article author does not speak for the RFPA.

Donate

Your contributions make it possible for us to reach Christians in more markets and more lands around the world than ever before.

Select Frequency

Enter Amount