Your cart is empty now.

October 15, 2020 Standard Bearer preview article

This article is written by Rev. Ronald Hanko and will be published in the October 15, 2020 issue of the Standard Bearer.

Click to read pdf as printed in the October 15, 2020 issue.

Click to read pdf as printed in the October 15, 2020 issue.

________________

Jonah

Introduction

The appeal of the book of Jonah, for this writer, lies in part in the character of Jonah. Disinclined to preach as sent, disobedient, grudging the repentance of those to whom he preached, Jonah shows himself to be a man “subject to like passions as we are” (James 5:17). Yet the prophet was used by God to save His people and to be, in history, an example of the power of God’s Word and the wideness of God’s purpose, even to be a pre-figure of the death and burial of our Savior. That “weakest means fulfill His will” (Psalter # 15; Psalm 8) is one of the minor lessons of the book, a lesson that continues to be taught in the use God makes of His people still today. May God so use each of us, poor sinners that we are, in His service and for His glory, whatever place and calling we have in His kingdom.

The author and main character

Whether Jonah is the author of the book we are not told. That is not impossible, though the book is written in the third person. Most of the prophets, major and minor, are the authors of the books that are named for them, but there is no direct proof one way or the other in this case.

The main character of the book is identified only as Jonah the son of Amittai. Of his father we know nothing; of him we know little. He prophesied during the reign of Jeroboam II and spoke of the expansion of the northern kingdom (Israel) during those days (2 Kings 14:25). He is further identified in II Kings as being from Gathhepher. Gathhepher is almost certainly the same town in the inheritance of Zebulun as Gittahhepher in Joshua 19:13, but identifying the two adds little to our knowledge of Jonah, except that he was probably a Zebulonite from the area later known as Galilee, a citizen of the northern kingdom, and one who was called to prophesy there.

As is often the case in the Bible, the personal details of the men God used are unimportant. What is important is the work God did through them, the messages they brought and the glory of the great salvation He revealed through them. Jonah himself does not matter very much. What matters is the wonderful demonstration God made through him of the eternal truth that “salvation is of the Lord” (Jonah 2:9).

The date

That Jonah prophesied during the reign of Jeroboam II means that he lived around 825 BC, about one hundred years before the demise of the northern kingdom. He was a contemporary of the prophets Hosea and Amos in the northern kingdom and perhaps of Isaiah in Judah. He prophesied at a time, therefore, when both kingdoms were strong and prosperous but at turning points in their histories. Both kingdoms had begun to decline and were soon swallowed up by the heathen kingdoms around them. This was especially true of the northern kingdom, which though outwardly strong, was spiritually rotten at the time of Jonah’s prophesy. Jonah’s disobedience is explained by the poor spiritual condition of the nation.

The historical background

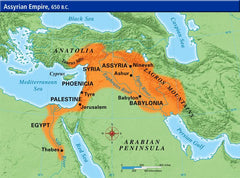

We do not know if Jonah prophesied before or beyond the rule of Jeroboam II. Jeroboam, the greatest king of the northern kingdom, was third in Jehu’s dynasty to rule that kingdom. Jehu had been promised four generations of rule over the northern kingdom, but Jeroboam’s son, Zachariah, would rule for only six months and the northern kingdom would begin its descent to anarchy and dissolution under him. Jeroboam, his father, restored the original boundaries of the kingdom, even conquering Damascus and Hamath, the great cities of the Syrian empire, adding them to his kingdom so that under his rule the ten tribes reached the height of their power and influence. During his reign Jonah prophesied and though Jonah certainly saw the prosperity of the kingdom under Jeroboam, there is no doubt he also saw its spiritual emptiness.

The prosperity and growth of the kingdom under Jeroboam were part of God’s mercy to that kingdom. Second Kings 14:26–27 tell us: “For the Lord saw the affliction of Israel, that it was very bitter: for there was not any shut up, nor any left, nor any helper for Israel. And the Lord said not that he would blot out the name of Israel from under heaven: but he saved them by the hand of Jeroboam the son of Joash.”

God was not being merciful to all in the northern kingdom, but there was still a remnant there (cf. the history of Elijah and Elisha) and to them God was merciful. It was shortly after Jonah that many who were left of God’s people in the northern kingdom migrated to Judah in connection with Hezekiah’s passover (2 Chron. 30:1–11). God showed them mercy in postponing the demise of their kingdom and in allowing them time for repentance. Perhaps they had heard the preaching of Jonah in their land.

For the most part Israel’s prosperity and growth during the reign of Jeroboam was only outward and superficial, for Jeroboam “did that which was evil in the sight of the Lord: he departed not from all the sins of Jeroboam the son of Nebat, who made Israel to sin” (2 Kings 14:24). Though the house of Jehu had destroyed the worship of Baal, they kept, under Jeroboam II and the others of Jehu’s dynasty, to the worship of the golden calves instituted by Jeroboam I as a substitute for the worship of God.

This spiritual destitution is important in the book of Jonah, for it explains Jonah’s reluctance to obey, his disobedience to God’s command, and his anger over Nineveh’s repentance. He saw Israel’s great spiritual need and grudged God’s grace to Nineveh, all the more so because Nineveh was an instrument of God in punishing Israel.

Nineveh’s place in history, as well as its repentance in the days of Jonah, explains Jonah’s reluctance, disobedience, and anger.

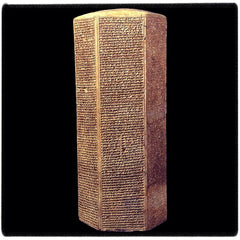

Nineveh, one of the great cities of ancient times, was the capital of Israel’s arch-enemy, Assyria. Assyria was becoming the world power of that day and was as given to wickedness as any of the great empires of ancient times. Zephaniah and Nahum would prophesy against Nineveh and Assyria, but she had been and would continue to be used by God to punish Israel’s wickedness by warring against, scattering, and taking into captivity that nation. No wonder, then, that Jonah begrudged their repentance.

The historicity

The historicity of the book is often questioned in connection with the story of Jonah being swallowed by a fish. The doubters are answered not only by the reference to Jonah in 2 Kings 14:25 but by our Lord’s comparison of His own burial to Jonah’s “three days and three nights in the whale’s belly” (Matt. 12:40). If Jesus believed that Jonah was an historical person, so must we. As someone said, “If God’s Word told me that Jonah swallowed a whale, I would believe that.”

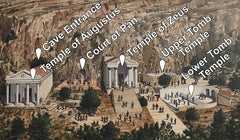

Jesus made further reference to Jonah (perhaps on the same occasion as in Matthew) in Luke 11:29–32 (cf. also Matt. 12:39–41):

And when the people were gathered thick together, he began to say, This is an evil generation: they seek a sign; and there shall no sign be given it, but the sign of Jonas the prophet. For as Jonas was a sign unto the Ninevites, so shall also the Son of man be to this generation. The queen of the south shall rise up in the judgment with the men of this generation, and condemn them: for she came from the utmost parts of the earth to hear the wisdom of Solomon; and, behold, a greater than Solomon is here. The men of Nineveh shall rise up in the judgment with this generation, and shall condemn it: for they repented at the preaching of Jonas; and, behold, a greater than Jonas is here (cf. also Matt. 12:39–41; 16:4).

He believed, as we must, that Jonah preached in Nineveh and that God used Jonah’s preaching to prefigure the salvation of the Gentiles.

The historicity of the book is important, not only because Jesus makes these references to Jonah, but also because the book shows so wonderfully that “salvation is of the Lord” (Jonah 2:9). It shows this in the Old Testament salvation of the Ninevites and in the salvation of a disobedient and reluctant prophet. To question the historicity of the book and to make the story a mere legend destroys that message.

The theme

The theme of Jonah is found in Jonah’s own confession that “salvation is of the Lord” (2:9). That theme is developed in God’s use of Jonah himself, in the repentance of the sailors who tossed Jonah overboard, in the salvation of Nineveh, as well as in Jonah’s own confession. It is further developed in the death and burial of Jesus, of whom Jonah, in that one thing, was a figure.

That theme may be said to be the great theme, even the only theme of the Word of God, illustrated in every story, song, and instruction of the Word of God. It is that lesson that we learn through trials and affliction and that will be our theme for eternity. That message ought to speak to the heart of everyone who sees himself in this reluctant and disobedient prophet, as well as to every Gentile believer whose repentance and salvation is as great a wonder as the repentance and salvation of the Ninevites.

The content of the article above is the sole responsibility of the article author. This article does not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of the Reformed Free Publishing staff or Association, and the article author does not speak for the RFPA.

Donate

Your contributions make it possible for us to reach Christians in more markets and more lands around the world than ever before.

Select Frequency

Enter Amount