Your cart is empty now.

Faith: A Bond, a Gift, and an Activity (5): Faith not as Condition

What follows is from Martyn McGeown's article "Faith: A Bond, a Gift, and an Activity, but Not a Condition for Salvation," published in the Protestant Reformed Theological Journal, April 2019, Vo. 52, No. 2. The article will be serialized on the RFPA blog. The previous entry is Faith: A Bond, a Gift, and an Activity (4): Salvation in Principle and in Reality.

__________

Many respond to this emphasis, which is a biblical and creedal emphasis, on the activity of faith, with the fear that the teaching that sinners must “do something” (that is, believe) to be saved makes faith a work on which salvation depends. They fear that it will lead to conditional theology, if it is not in fact already conditional theology.

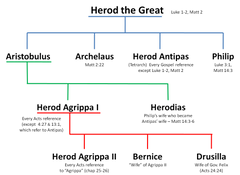

In the midst of the conditional covenant controversy that erupted in the PRCA during the 1950s, Hubert DeWolf, one of the three pastors of the First Protestant Reformed Church, of which Herman Hoeksema was also a pastor and member, uttered the infamous words: “Our act of conversion is a prerequisite to enter the kingdom.” Is the insistence that the sinner must believe in Christ to be saved, that is, to come to the conscious knowledge and enjoyment of his salvation, especially his justification, not a similar error to the conditional theology of DeWolf? To understand the difference we should briefly examine the ecclesiastical judgment rendered in the DeWolf case and explain the nature of conditions. Without a definition of “condition,” we are liable to go astray.

Classis East (1953) ruled on DeWolf’s “prerequisite” statement:

[This statement means] that we convert and humble ourselves before we are translated from the power of darkness into the kingdom of God’s dear Son, while Scripture and the confessions clearly teach: that the whole of our conversion… [in] which we humble ourselves, is sovereignly wrought by God, by His Spirit and Word through the preaching of the gospel in His elect … This entire work of conversion is our translation and entering into the kingdom of God. Hence, it is not, cannot be before, but THROUGH our conversion that we enter the kingdom … Our ACT of conversion is never antecedent to our entering in, but always is performed IN the kingdom of God, and there are no prerequisites.[23]

Classis East of the PRCA (1953) appealed to Colossians 1:12-13, where the apostle is referring to regeneration, not justification: “Giving thanks unto the Father, which hath made us meet to be partakers of the inheritance of the saints in light: who hath delivered us from the power of darkness, and hath translated us into the kingdom of his dear Son.” In addition, Hoeksema in his “Hull Mass Meeting” of 1953, in discussing the heretical statement, appeals to John 3, where Christ refers to regeneration. We do not enter the kingdom by justification or by conversion (including our activity of believing and repenting), but by regeneration. And remember that the jailor, for example, to whom the command to believe came, was in the kingdom already, that is, he was regenerate.

In that “Hull Mass Meeting” of 1953, at approximately the twenty-nine minutes mark, Hoeksema, in discussing DeWolf’s statement, says: “He did not say, ‘I preach to you the promise that, if you believe, you shall be saved.’ That would have been not quite clear, but it would have passed muster.”[24] The issue was that DeWolf said, “God promises to everyone of you that, if you believe, you shall be saved.”

Hoeksema did not condemn the word “if.” He condemned the word “prerequisite.” Hoeksema could not have condemned the word “if” because he knew that the Bible uses the word “if” (John 15:10, 14; Rom. 11:22; II Tim. 2:12). Hoeksema knew that sentences with the conjunction “if,” although they are grammatically conditional in form, do not imply conditional salvation. Instead, the “if clause” has two functions: first, it identifies the recipients of salvation: in John 15:10 those who abide in Christ’s love are those—and only those—who keep His commandments; and in John 15:14 those whom Christ calls His friends are those—and only those—who do whatever He commands them. Second, the “if clause” motivates the hearer to obedience, for God uses warnings on the one hand, and the promises of rewards on the other hand, to motivate his children; godly parents do the same thing. A third connected purpose of “if clauses” is to separate the hearers or to sift the audience: the command comes to all, but by it God works the positive response of faith and repentance in the elect, while He hardens the reprobate and leaves them inexcusable. Commands and “if clauses” are prods to stir us up to new faith and obedience. We need them because we are so sluggish through the weakness of the flesh; it would be perilous to our salvation for the preacher to omit warnings, exhortations, and sharp applications. The fathers at Dordt understood this very clearly: “And as it hath pleased God, by the preaching of the gospel, to begin this work of grace in us, so He preserves, continues, and perfects it by the hearing and reading of His Word, by meditation thereon, and by the exhortations, threatenings, and promises thereof, as well as by the use of the sacraments” (Canons 5, 14). The same Canons describe the neglect of such sharp, pointed preaching, including exhortations and threatenings (as mandated in Heidelberg Catechism, Q&A 115) as “[the presumption] to tempt God” (3-4, 17).

It is interesting to note that the antinomian party of Anne Hutchinson (1591-1643) in New England “denied all commands and exhortations.”[25] To them “even the gospel command to believe in Jesus Christ for salvation is a law, and therefore, is illegitimate. If a preacher does give this command, the command will not bear the fruit that anyone believes. Rather, the command [to believe] only ‘killeth.’”[26] According to Hutchinson, “[the believer] cannot believe. He is not to be exhorted to believe. But Jesus believes for him. If there is some faith in the child of God, it is Jesus believing in him, not his own believing.”27

Therefore, when (not—“if”) a preacher preaches such “if” texts, he should not spend most of the sermon explaining away the text, so that the sharpness of the exhortation or warning is lost. The preacher should not be afraid to use the “if” word, lest someone think that he is guilty of preaching conditional theology. By running scared of conditional grammar, he plays into the hands of the men of the Federal Vision—what defence will he have when the members of his congregation come across that false doctrine if he has taught them to view “if” as a bogeyman?

As an example of how this is done, I quote from a sermon that David Engelsma preached at the British Reformed Fellowship Conference, which sermon was later edited for publication:

This instruction and admonition are important. The importance of hearing this instruction and heeding this admonition is that a holy life is a necessity. It is a necessity for final salvation, according to the text itself (1 Cor. 6:9-11): the unholy person shall not inherit the kingdom of God. There is the danger that this necessity is explained wrongly, even heretically. This would be the explanation that by our holiness we ourselves earn final salvation. Or it would be the explanation that our holiness is a condition that we must perform in order to obtain final salvation … Such is the necessity of holiness of life that no unholy person shall receive this final salvation in the day of Christ: ‘Without which [holiness] no man shall see the Lord’ (Heb. 12:14). Positively, such is the necessity of holiness that only the holy man or woman shall be saved in the day of Christ. All those who were, and remained, un- holy will be condemned, damned and lost outside the kingdom in the outer darkness of hell. All such will be excluded from the kingdom of God … The warning has practical benefit. It is a means of God’s sanctifying us. The warning motivates us to fight our sinful, unholy nature, and to strive after holiness. The warning motivates one who is presently living impenitently in one of the sins mentioned in the text, or any other sin, to repent, be forgiven and begin again to live a holy life. And the warning moves us to be thankful to God in Christ for the saving work of sanctification in our life.[28]

Herman Bavinck, a Dutch theologian who resolutely rejected conditional theology and who taught an unconditional covenant governed by election, also offers helpful insights into the conditional-sounding language in which Scripture sometimes presents the covenant. While Bavinck rejects “conditions” in the conditions, as activities of the sinner on which salvation in the covenant depends, he still does justice to the language of the Bible. Engelsma quotes Bavinck:

Bavinck will speak only of the “conditional form” of the administration of the covenant: “In its administration by Christ, the covenant of grace does assume this demanding conditional form.” By a conditional form, Bavinck refers, among other constructions, to the biblical exhortations and admonitions that use the conjunction ‘if’… A conditional form of the administration of the covenant is not the same as a conditional covenant. The conditional form of the administration of the covenant does not mean, for Bavinck, demands for a human work upon which the covenant depends, or for a human work that must make impotent covenant grace effectual in the case of the one performing the work. The conditional form of the administration of the covenant rather refers to God’s dealings with “humans in their capacity as rational and moral beings … to treat them as having been created in God’s image; and also … to hold them responsible and inexcusable; and finally to cause them to enter consciously and freely into this covenant and to break their covenant with sin.”[29]

What, then, is a condition—and how can one detect the real threat of conditional theology? The main elements of conditional theology are these three. First, the covenant is deliberately severed from election. The Protestant Reformed Churches and her sisters gladly teach that election governs the covenant and that only the elect are in the covenant. Second, God promises salvation to all the children of believers, whether elect or reprobate, on condition of faith. The Protestant Reformed Churches and her sisters vigorously defend the unpopular position, faithful to Scripture and the creeds, that God promises salvation only to the elect and included in that promise is faith itself (Heidelberg Catechism, A. 73). Third, the promise of salvation, although sincere on God’s part, is not fulfilled in those who do not believe, and therefore it fails. The Protestant Reformed Churches and her sisters teach that God’s promise of salvation cannot fail and that it cannot remain unfulfilled in any of God’s elect (Rom. 9:6).

Klaas Schilder, the theologian who more than anyone else injected conditional theology into the Protestant Reformed Churches in the 1950’s, was notoriously unclear in his definition of “conditions” in the covenant.

“Condition” in liberated theology is merely “means for the execution of the decree of ELECTION.” A ‘condition’ is merely “the way by which the elect come to and are assured of salvation… God… does not give B without A, C without B, and D without C.”[30]

These words above do not in themselves constitute conditional theology. Nevertheless, Schilder’s underlying theology was objection- able to Hoeksema and to the Protestant Reformed Churches, although strangely alluring to DeWolf and his allies.

Of course, if this is what “condition” means in the covenant theology of the liberated Reformed, the Declaration [of Principles] is confused and mistaken in its opposition to conditional covenant theology. What Reformed church or theologian denies that faith is the “way” to forgiveness and salvation, or that God follows a certain “order” in his salvation of his people in the covenant?[31]

Indeed, what Reformed church or theologian denies that faith is the way to forgiveness and salvation? Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ and thou shalt be saved, and thy house! We must never be afraid to preach in those terms—afraid to call unbelievers to the act of faith in Jesus Christ for fear of preaching conditions. Such a fear would cripple preaching not only on the mission field, but also in the established congregations. Such a fear would muzzle the preacher from making sharp warnings and applications, lest his words sound like conditional theology. Such a fear would betray not an incipient conditional theology, but an incipient hyper-Calvinism, a charge that the enemies of the Protestant Reformed churches have hurled at her and her sisters for many years, and one that they have consistently rebuffed.

Hoeksema explained the matter of conditions in the Standard Bearer in April 15, 1950, a few months before the synod at which the Protestant Reformed Churches provisionally adopted the Declaration of Principles—vintage Hoeksema, therefore. He writes, “[A condition] is something that must be fulfilled prior to something else” or “[it is] something demanded or required as a prerequisite to the granting or performance of something else.” In the same article, Hoeksema writes positively about the relationship between faith, election, and salvation:

God is first in the calling, and man obeys the calling as the fruit of the work of God in him” and “there are no antecedent conditions which man must fulfill in order to receive that faith or the gift of active belief. God causes him to become an active believer… Never is any work or act of man prior to the work of God, but always the act of God is first. And by virtue of the work of God in him can the sinner become active.

In the same article, with his eye on Canons 3-4, 16, Hoeksema denies that man is a senseless stock or block in salvation:

[Man] is freely responsible for the new obedience unto which he is called. Just because God works within him to will and to do of his good pleasure, he heeds the admonition to work out his own salvation…God regenerates them, and they live. God calls them, and they come. God gives them faith, and they believe. God justifies them, and they are righteous. God sanctifies them, and they walk in a new and holy life. God preserves them, and they persevere even unto the end. And all this work is without condition. That is the relation between the work of God and our work.[32]

These statements of Hoeksema are also reflected in “The Declaration of Principles,” of which he was the principal author, and which document includes a section about responsibility, which is not the same as conditionality:

The sure promise of God which he realizes in us as rational and moral creatures not only makes it impossible that we should not bring forth fruits of thankfulness but also confronts us with the obligation of love, to walk in a new and holy life, and constantly to watch unto prayer. All those who are not thus disposed, who do not repent but walk in sin, are the objects of his just wrath and excluded from the kingdom of heaven … The preaching comes to all; and … God seriously commands to faith and repentance; and … to all those who come and believe he promises life and peace.[33]

Commenting on this important document, Engelsma drives home the responsibility of the believer in the covenant:

God commands his covenant friends to pray. The Catechism teaches also that the way of salvation is a way of sincere, diligent, spiritual activity. Sovereign grace does not nullify responsibility; it maintains responsibility… The grace of God in Jesus Christ (which is covenant grace), treating men and women as rational moral creatures (“not… as senseless stocks and blocks”), irresistibly makes the objects of this grace alive and willingly, actively holy. In this work of sanctification, God uses the means of the gospel, with its “precepts” and “admoni- tions.” This confessional proof guards against misunderstanding and abuse of the truth that the covenant promise is unconditional to the elect children of believers. Thus godly parents, trusting God’s promise to save their children, will not avoid sharp warnings to their children (as though warnings would compromise grace) but will use them in the rearing of their children (as grace employs warnings to accomplish the purpose of the salvation of the children). The same holds true of good Reformed pastors with regard to their congregation. The notion that admonitions are unnecessary is a form of the antinomianism and hyper-Calvinism that the Declaration rejects.[34]

When one emphasizes that the work of God is first, and that the subsequent response of active, conscious faith is the fruit of God’s particular, efficacious grace in the sinner, one does not teach conditional theology, even if one uses the biblical conjunction “if.”

In light of the confusion and controversy that swirls around the idea of demands in the covenant and conditional language, perhaps it is time for the theologians of the Protestant Reformed Churches and her sisters to heed Engelsma’s plea:

We must develop this doctrine of the covenant. We must develop it with regard to the demand of the covenant upon the members, with regard to the warnings, with regard to the full, active life of the covenant, with regard to covenant obedience and covenant unfaithfulness on the part of the covenant people, with regard to the important part of the people of God in the covenant, with regard to divine rewards and chastisements, with regard to the genuine mutuality of the covenant. All of these aspects of the full reality of the covenant, and more, must be developed not in tension with election, certainly not in contradiction of election, but in harmony with election, as the very outworking of the eternal decree.[35]

[23] Quoted in Engelsma, Battle, 105 (Upper case letters in original).

[24] The Hull Mass Meeting (1953), https://www.sermonaudio.com/sermoninfo.asp?SID=46121146431

[25] Engelsma, Be Ye Holy! The Reformed Doctrine of Sanctification (United Kingdom: British Reformed Fellowship, 2016), 79.

[26] Engelsma, Be Ye Holy! 79 (My italics).

[27] Engelsma, Be Ye Holy! 79 (My italics).

[28] David Engelsma, “Only the Holy Inherit the Kingdom,” in Be Ye Holy!,102, 107, 110 (My italics).

[29] Engelsma, Covenant and Election in the Reformed Tradition (Grandville, MI: Reformed Free Publishing Association, 2011), 170-1.

[30] Engelsma, Battle, 179 (Upper case letters in original quote by Schilder).

[31] Engelsma, Battle, 179.

[32] Herman Hoeksema, “As to Conditions,” Standard Bearer (April 15, 1950).

[33] Engelsma, Battle, 43.

[34] Engelsma, Battle, 261-2 (My italics).

[35] Engelsma, Covenant and Election, 226-77 (My italics).

End of the series

The content of the article above is the sole responsibility of the article author. This article does not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of the Reformed Free Publishing staff or Association, and the article author does not speak for the RFPA.

Donate

Your contributions make it possible for us to reach Christians in more markets and more lands around the world than ever before.

Select Frequency

Enter Amount