Your cart is empty now.

Christ and His Church Through the Ages: Vol. 1 - A Review

What follows is a review by Rev. Martyn McGeown of Christ and His Church Through the Ages: Vol. 1: The Ancient Church (AD 30-590), written by Herman Hanko.

_______________

Dan VanUffelen, teacher of church history at Covenant Christian High School in Michigan USA, with the collaboration of one of the author’s granddaughters and with the help of many others, has achieved his dream: “a layman’s guide to church history, a textbook for both old and young that [celebrates] the great doctrine of sovereign grace and [traces] the history of the church from the days of the apostles through the history of the Protestant Reformed Churches” (xiii).

The author is the towering and much beloved figure of Prof Herman Hanko, who served in the office of pastor from 1955-1965 and then in the seminary as professor of New Testament and Church History from 1965-2011 when he “retired.” Of course, Prof has never really retired—he still writes—and VanUffelen desperately wanted the (then) almost octogenarian Hanko to write another book on church history for the benefit especially of the high school students whom he taught and teaches.

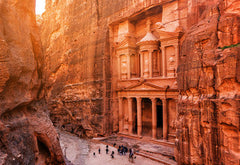

Volume one covers the first major period of church history, ancient church history (AD 30-590). Beautifully illustrated within and without, this book does exactly what VanUffelen desired—and more. It recalls in exciting prose the thrilling story of Christ’s church, as our sovereign Father determined that history for the glory of his name, the salvation of his people, and the ripening of the reprobate wicked in sin, which ripening also serves the salvation of the church and the glory of the triune God.

Hanko writes with infectious enthusiasm for his subject, which is not dull history, but the history of the church, which, Hanko reminds us, is the center of history. Church history is the center of history because the church is the church of Jesus Christ, who is the center of history.

This history book is a Christocentric (Christ-centered), and therefore, a theocentric (God-centered), account of the events of the ages. Writes Hanko, “We must see Christ’s sceptre swaying in all the events of time. But we must see that it sways for the realization of Christ’s kingdom that the elect shall inherit” (4). Proud kings, cruel emperors, and even wicked heretics strut the world’s stage for the sake of the church, for her salvation, and ultimately for God’s glory. Nothing happens by chance and nothing happens unrelated to Jesus Christ. How many history books, even church history books, are written from that glorious perspective? But that—and only that—is the biblical and Reformed perspective of history. The author even provides the reader with a definition of church history:

Church history, narrowly defined and in distinction from sacred history, is God’s revelation of his sovereign, infinitely wise, merciful, just, and all-embracive counsel regarding Christ’s church on earth, from the death of the last apostle to the second coming of the Savior. It is thus a biography of the church—of her development both normal and abnormal; of her life, activity, and tribulations in the world; and of her physical, intellectual, and ethical forces within the limits above specified (6).

For many of us the only church history we know well—and the only part in which we are interested—is the Reformation. That is a mistake, for ancient church history includes exciting and formative years, even centuries. To the ancient church belong such heroes as Justin Martyr, Polycarp, Ignatius, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Athanasius, Chrysostom, Ambrose, Augustine, and St. Patrick; and such villains as Valentinus, Marcion, Montanus, Diocletian and Galerius, Julian the Apostate, Arius, Nestorius, and Donatus. Hanko has also written about many of those figures in his Portraits of Faithful Saints (RFPA: 1999) and Contending for the Faith (RFPA: 2010).

To help the reader get his bearings in perhaps unfamiliar history, and to make the book useful in the classroom for high school students, the material is neatly divided into three main sections. The first section treats the apostolic period (30-100 AD), which, strictly speaking, is still biblical history. In this period God, through his apostles, provides the foundation for the church in doctrine, government, and worship. That period ended with the death of John, the last apostle. The second section covers the post-apostolic period (100-313 AD), which is characterized especially by persecution and heresy, the two fronts of the devil’s attacks, but which simply constituted the crucible in which the church, tried as by fire, came forth as gold. That period ended when Constantine granted freedom and toleration to the hitherto persecuted church. The third section of the book is devoted to the Nicene and Post Nicene periods (313-590 AD) during which time the church was again convulsed by major heresies, controversies, and schisms. Arianism, the Christological controversies, and the Donatist Schism belong to that third period, when men such as Athanasius, the Cappadocian fathers, and Augustine defended and developed the truth.

The church is built upon the truth taught by the prophets and the apostles. Therefore, the struggle of the ages—and especially of the early period—is the battle between the truth and the lie. After the death of the apostles and the completion of the canon of Scripture the church was called to define and defend the truth, something she did because the Spirit guided her into all truth, as Christ had promised (John 16:13). Nevertheless, the way by which the Spirit guided the church was not easy. On the one hand, the church was assailed by Jews and pagans, enemies outside. Early Christian thinkers called Apologists (an apology is a defence) played an important role, although they were not altogether free of the influence of pagan philosophy. We tend to romanticize the early church: she was, in fact, made up of sinners; and her theologians, many of whom died as martyrs, struggled to understand the truth. We are the heirs of some two thousand years of doctrinal development; they were not. Hanko explains:

The church was a theological infant in the first centuries, and leaders in the church did not have a clear understanding of all the truths of scripture. The church fathers themselves, struggling to understand the truth more fully and trying to find ways to express the truth more clearly, often made mistakes in their teachings. If these mistakes were taught today, they would be considered heresies, but early in the life of the church this was not so (71).

It is striking, by the way, that the early church did not look to some infallible leader, such as the bishop of Rome, to help her define the truth. She sought truth in the Bible, for that is where God has deposited it. In fact, the bishop of Rome was often on the wrong side of theological debate in the early church and he only gradually rose to prominence and dominance. For example, Zosimus (r. 417-418) wrongly sided with Pelagius and Celestius, declaring them orthodox, but when the African bishops, who had condemned Pelagius and Celestius, objected, Zosimus changed his mind, “a change of mind that makes mockery of claims to papal infallibility in matters of doctrine” (205).

On the other hand, the church faced heresies and heretics from within. Heresies have a good purpose. Hanko explains what a heretic is—and what heresy is not. A heretic is not simply someone who makes a theological mistake, or someone who articulates the truth wrongly. Church history is full of such people: perhaps we scratch our heads when we read theologians of the past, but they are not necessarily heretics. Heresy is error taught wilfully, deliberately, and persistently, especially in defiance of the church. “Heretics,” writes Hanko, “know the truth, but either they do not want it, or they are so conceited that they are willing to sacrifice the truth on the altar of their own pride. Even when the church shows them that they teach contrary to scripture, they cling to their false doctrine” (73). Heretics are almost always motivated by pride. They insist against the authority of the church that they know better and they refuse to change when they are corrected. A meek man who submits to ecclesiastical correction is not a heretic—he may be wrong, but when he reveals a teachable spirit, he shows himself not to be a heretic. Hanko describes Arius, one of the chief heretics of this period:

Arius was known for his asceticism and his courtly manners. He was tall and thin and had the general appearance of a scholar. He was a man of ability, learning, and piety. He made a favorable impression of the people whom he met. But beneath his external demeanor was a burning pride (147).

Apollanaris, who denied that Jesus had a human spirit or mind (which, he said, was replaced by the divine Logos), is another example. He made, at first innocently, some theological errors in his attempt to explain the two natures of Jesus Christ, but when the church pointed out that his error was really a denial of the complete humanity of Christ, and he stubbornly persisted in his error, then he became a heretic:

Up to this point, Apollinaris was incorrect, but he was not a heretic. He was wrong, but not sinful. His views were condemned… When it condemned Apollinaris’s views, it made the condemnation of Apollinarianism the official teaching of the church; and when Apollinaris still insisted on his error after it was shown to conflict with scripture, he became a heretic (160-161).

So today, the church does not condemn a man—a minister or an elder—for a false statement, unless it is something that the church has already officially condemned, unless the man refuses to repent of his error, and unless the man (after the authorities of the church, especially his consistory and the other assemblies, have carefully worked with him) persists in his error. Then, and only then, is he to be condemned as a heretic or a teacher of false doctrine in the church. The church must be patient with those who err in doctrine or in life: excessive rigor is unbecoming of the church of Jesus Christ.

Sometimes God used unpleasant characters in the defense of the truth. Hanko writes about Nestorius and Cyril. Nestorius denied the unity of Christ’s two natures, teaching that there are two persons in Jesus Christ. Hanko describes the man as “unbearably vain, a superficial thinker, impetuous, and intemperately hostile” (161). Cyril, his theological opponent, whose views won the day, was “shrewd, haughty, selfish, and ready to use means fair and foul in his efforts to overthrow Nestorius” (162).

Both the outstanding men in the controversy were notorious for their ugly characters and were wrong in their theological positions. Only God could make something good emerge from the mess… Cyril and Nestorius were like two boxers in a ring, both so utterly distasteful that one can hardly decide for whom to cheer (161-162).

Another danger for the church in this period was schism. If the calling of believers is “to keep the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace” (Eph. 4:3), then schism, which is a sinful rending of the church is lamentable. Two similar schisms took place in the early period: the Novatian and the Donatist schism, and both happened because of a refusal to do what the apostle urges: “Let all bitterness, and wrath, and anger, and clamour, and evil speaking, be put away from you, with all malice. And be ye kind to one another, tenderhearted, forgiving one another, even as God for Christ’s sake hath forgiven you” (Eph. 4:31-32). The occasion for both schisms was persecution and the question of the so-called lapsed, of those who had renounced the faith to save their own skin. Would the church allow such people to be members again if they sought readmission to the fellowship of believers after the persecution had ended? That was a controversial question: should men who had denied Jesus be allowed to sit down in fellowship and even at the Lord’s table with men who still bore in their bodies the marks of the torturers? The Donatists refused to allow such men (whom they called traditors—or traitors) membership or to hold office in the church, even if they repented; and they split the church over it, thus evidencing the awful character of the Unmerciful Servant in Matthew 18. Hanko warns that the church must receive penitent sinners:

Scripture makes clear that the church of Christ must receive the confession of sin that a sinner makes (Matt. 18:15-35). No one can judge the heart except God. The elders must take a sinner at his word and leave the matter with God—unless the sinner gives clear evidence that his confession is not sincere. But it must be remembered that true confession implies repentance, and repentance implies forsaking sin (114).

The warning for the church is that it must not judge who are tares and who are wheat. God will take care of that. It is the calling of the church to forgive sin, no matter how great, and to bring repentant sinners back into the church; but never to judge the heart, unless it be with the judgment of love (198).

Throughout this book Hanko emphasizes the absolute sovereignty, the perfect wisdom, the unfailing faithfulness, the rich mercy, and the particular grace of God in church history. In early church history, as the author explains, God is laying the foundation for the church of later years; while at the same time, also according to the inscrutable will of God, the church is sowing seeds of error and corruption (Semi-Pelagianism, monasticism, and hierarchy, for example), which will bear bitter fruit in later years, especially in the medieval period. God does this always out of love for her church, to gather her, to defend her, to teach her, and even to purify her through chastisement. At many points, Hanko asks, “What was God’s purpose in this event?” The heresy of Gnosticism, for example, “forced the church to consider the relationship between pagan and mystical thought on the one hand and the Christian faith on the other” (85). Arius, another example, “was a goad to compel the church to define [the biblical doctrine of the Trinity] so that it could be established for all time” (156). God even used the grossly immoral youth of Augustine for the development of doctrine:

His deliverance from an immoral life, which he had so much difficulty resisting, was to Augustine a testimony to the power of grace and the inability of man to do anything to save himself. As God used the apostle Paul’s early life of rebellion against Christ to prepare him to be a missionary to the Gentiles, so God used Augustine’s sinful life to lead him to the doctrines of sovereign grace (202).

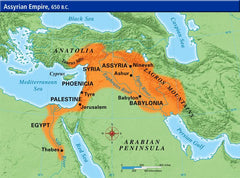

VanUffelen, who edited and revised the work, has added helpful charts, maps, timelines, and illustrations, which greatly enhance the book. This is a great read and will appeal even to children: I have already heard of one nine-year old boy who “loves it.” May the Lord use it for the edification especially of Christian youth in the schools, for the instruction of God’s people everywhere, and for his own glory! May it serve as a family history for the church of which all believers are members! I look forward to the next volumes.

Also available in ebook format!

The content of the article above is the sole responsibility of the article author. This article does not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of the Reformed Free Publishing staff or Association, and the article author does not speak for the RFPA.

Donate

Your contributions make it possible for us to reach Christians in more markets and more lands around the world than ever before.

Select Frequency

Enter Amount