Your cart is empty now.

Book Review - The Savior's Farewell

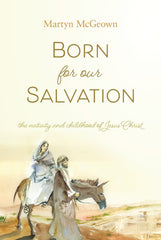

The following review was written by Roger G. DePriest of Virginia Beach Theological Seminary, Virginia Beach, VA, on the book The Savior’s Farewell: Comfort from the Upper Room, by Martyn McGeown (Jenison, MI: Reformed Free Publishing, 2022). This review was originally published in the Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal.

The author of this volume, Martyn McGeown, is a graduate of Protestant Reformed Theological Seminary and was ordained by the Covenant Protestant Reformed Church in Northern Ireland, where he pastored from 2010 until he immigrated to the United States in 2019. In fact, this book was adapted from a series of messages on John 14–16 which he preached to his congregation in Limerick, Ireland, over a period of seven months. In its own way, those sermons, which form the core of this book, were his own farewell message to his Irish congregation.

The book is divided into three parts: “Part 1 (John 14): The Disciples’ Advantage in Jesus’ Departure”; “Part 2 (John 15): Spiritual Fellowship with Jesus Christ”; and “Part 3 (John 16): Warnings and Encouragement about the Future.” The author’s pastoral heart comes through clearly in each of the book’s twenty-six chapters. Although he comments on every verse in these three chapters, it is not quite accurate to call this a commentary, since there is little by way of formal introductory matters (viz., authorship, date, genre, etc.). That is not to say, however, that the author does not grapple with weighty matters. One of the most profound and profitable chapters was on the Holy Spirit’s procession from the Father and the Son (i.e., the filioque controversy, 231–42). McGeown has made a very complicated theological matter accessible to the lay person.

Although McGeown does not expressly state his thesis within the body of the work, both the title and subtitle suggest it: The Savior’s Farewell: Comfort from the Upper Room. With the use of “Farewell” in the title, Johannine scholars will recognize that the author tips his hat to the Testament genre (also known as Farewell Discourse genre, e.g., Gen. 49; Josh. 22–24). Unfortunately, he does not inform the reader of any of these distinctive features, of which there are several. Nevertheless, he still achieves the aim of identifying how Jesus comforted his eleven disciples and then applied those observations to contemporary disciples of our day who find themselves engulfed in fear, loss, and uncertainty.

One of the author’s strengths is his regular reach into the historic creeds and confessions of the church. Let me illustrate with how McGeown handles the oft-debated treatment of what it means to “abide” in John 15. He writes, “Abiding in the vine, therefore, is not the same as doing good works. There is some confusion here…Fruit depends on union with the vine. Union with the vine does not depend on fruit” (139). Then comes his segue: “Consider a number of creedal references in connection with this” (140). What follows over the next two pages are three citations from the Belgic Confession and four from the Heidelberg Catechism.

To be sure, McGeown’s work is a treasure trove of exegetical and pastoral insights, and, from that interest alone, pastors will want to lean into this resource. There are several places, however, where those who do not share the Reformed hermeneutic (such as this reviewer) will find reasons to balk here and there. This is because McGeown stands firmly in the Reformed camp, so it is to be expected that his theological commitments will inevitably show. And they show in places one would most likely anticipate, namely, in areas of theological distinctives, especially regarding ecclesiology and eschatology. For example, besides an explicit reference to the “covenant of grace” when discussing election in John 15:16 (“ye have not chosen me, but I have chosen you”), he also identifies the elect as “believing people, and their elect children” (192), that the church did not begin at Pentecost since it existed during the Old Testament (310), and that Jesus’s kingdom was not physical but spiritual (32). This may cause some pastors outside the Reformed camp to either withhold endorsements to their flock or to do so only with a caveat, so as to prevent potential confusion.

Despite the abundance of profitable insights, there is one doctrinal aberration that is repeated many times throughout the book. McGeown argues that the term “Father” in reference to divinity has two distinct meanings. In the first meaning, it refers to the first person of the Trinity. No problem there. It is the second meaning that is idiosyncratic—at least this reviewer has never encountered such a view before. He argues that sometimes the term “Father” (with reference to divinity) is a reference to the triune God. One could furnish many examples of this throughout his book, but just a few will suffice. In discussing John 14:7–11, and the exchange Jesus had with his disciples about seeing the Father, he states that the “Father is also a reference to the triune God, or to the Godhead without distinction of persons” (37). He then explains that the basis for this is the incarnation of God the Son (39). Elsewhere he writes, “When Jesus lived on earth, he prayed to the triune God, and he obeyed the law of the triune God…In summary, God is Father, first, as the Father of the Son, in the being of the Trinity; second, as the triune Father of the incarnate Son” (75). This is theologically problematic.

Without question, McGeown has made a worthy contribution to Johannine literature. Yet it is difficult to position it precisely in terms of its primary audience. Because it is an adaptation of sermons to a local congregation, the target audience is for the church. But it is more suitable for mature believers, given its often weighty and theologically dense discussions. Since there is no backmatter, only a brief introduction (5 pages) following the Table of Contents and very few footnotes, scholars may wish for access to his source material, while at the same time finding it profitable in many ways.

Roger G. DePriest

Virginia Beach Theological Seminary, Virginia Beach, VA

Click the image or this link to order the book reviewed in this post!

The content of the article above is the sole responsibility of the article author. This article does not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of the Reformed Free Publishing staff or Association, and the article author does not speak for the RFPA.

Donate

Your contributions make it possible for us to reach Christians in more markets and more lands around the world than ever before.

Select Frequency

Enter Amount