Your cart is empty now.

"As in the Days of Noah..." (5)

By Rev. Daniel Holstege. Previous article in the series: "As in the Days of Noah..." (4)

_________

The final topic I am going to treat from the days of Noah is the covenant that God established with Noah after the flood (Gen. 9:8-17). In his book De Gemeene Gratie, first published in Dutch in 1902 in the Netherlands, Abraham Kuyper proposed that the covenant God made with Noah is the “mighty, majestic, predominant starting point for the entire developmental history of our human life. By means of that starting point with Noah, common grace, which began in Paradise, acquired its more definite form” (Common Grace: Noah to Adam, Volume 1, Part 1, p. 23). Kuyper wrote that “we are not dealing here with a covenant of particular grace, but a covenant of common grace” (p. 28). He considered the history in Genesis 9 an irrefutable argument for his whole theory of common grace. After all, God promised to establish his covenant with Noah and his seed, and who can deny that the seed of Noah refers to all men who ever lived since the flood? Therefore, this covenant with Noah is distinct and broader than the later covenant with Abraham, and it has nothing to do with salvation but only the preservation and flourishing of human life on earth in this present time. Many Reformed men on both sides of the Atlantic heartily agreed with him.

But in the early 1920s, two Christian Reformed ministers named Henry Danhof and Herman Hoeksema “criticized Kuyper’s reasoning with respect to this covenant with Noah” (see “Not Anabaptist But Reformed,” in The Rock Whence We Are Hewn, pp. 94-106). They argued strenuously that the covenant with Noah was “a phase of the development of the covenant of grace,” (God’s one covenant of particular grace). In the covenant with Noah, God teaches us that his one covenant will extend to “all generations of the earth, upholding all that exists in time” (p. 94), and will include “the entire human race, for God is speaking to Noah and his sons” (p. 100). But when God established his covenant with Noah and his seed, this must be understood “organically” because throughout Scripture it “never pertains to every person among that seed” (p. 99). They pressed their argument further: “How could you have a type of baptism in the flood, and a type of God’s church as it passes through baptism and arises with Christ in the ark, if you make all of this universal? … The people with whom he establishes his covenant after the flood are his covenantal people, always taken organically” (pp. 104-105).

Let me try to explain this a bit more.

First of all, it is true that after the flood God promised to maintain regular patterns in nature so that “while the earth remaineth, seedtime and harvest, and cold and heat, and summer and winter, and day and night shall not cease” (Gen. 8:22), nor “shall there any more be a flood to destroy the earth” (9:11). We reject the unbelieving uniformitarianism of the scoffers of our day who say that all things continue as they were from the beginning of the creation and who deny that God fundamentally transformed the world by sending the flood. But we heartily confess that since the flood God himself maintains the regular patterns of nature that we observe by his marvelous providence and gives to all mankind the gifts of life, and breath, and all things. I was struck by this when I preached through this part of God’s word recently. I knew well that we reject the uniformitarian theory of fixed laws of nature holding sway since the “Big Bang.” But a piece of the puzzle was put in place for me when I realized the reason we see the forces of nature behaving in such predictable ways today is that God himself promised to maintain regular patterns after the flood as long as the earth remains. But should we call that a common grace of God to all men that saves no one (that being the purpose of particular grace) but only preserves and promotes human civilization in this present time as an end in itself? No, but we should recognize it as the providence of God which serves the salvation of his church with a view to the glorious creation of the world to come.

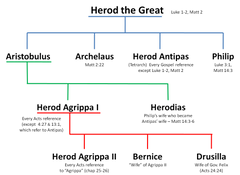

Secondly, then, the covenant that God established with Noah and his seed after the flood was a significant phase in the revelation of his one everlasting covenant. God had already established his covenant of friendship with Noah and his sons before the flood, which explains the fact that “Noah walked with God” (Gen. 6:9). But then God saved Noah, his family, and at least two of every kind of living creature on earth in the ark through the waters of the flood, carried them into the newly cleansed world, and promised to establish his covenant with them. When it came to Noah and his family, God was promising to maintain the very same relationship that he had already established with them, in which he was their God and they were his people. When it came to their “seed” after them, God did not mean all of their offspring head for head but all whom he had given to Christ before the foundation of the world and of whom Christ himself is the chief seed. What Paul wrote about the promise of God to Abraham applies also to his promise to Noah: “He saith not, and to seeds, as of many; but as of one, and to thy seed, which is Christ” (Gal. 3:16). Moreover, as Hoeksema and Danhof also were quick to add, the fact that God spoke this promise to Noah and his sons and their seed teaches that his covenant in Christ would indeed extend to “the entire human race” as it flowed out of Shem, Ham, and Japheth. Hence our mission mandate to go into all the world and preach the gospel of Christ to all nations.

Thirdly, what makes this phase of the establishment of God’s covenant particularly beautiful and marvelous is that it reaches out to the whole earth and to every living creature that is upon the earth… the singing birds of the air, the grazing cattle upon a thousand hills, the pride of lions on the savannah… But how can God have fellowship with brute beasts? When God established his covenant with the animals, that relationship was unique to their natures, meaning God does not have communion with them as he does with us, but he cares for them in his love with a view to their future participation in the glorious liberty of the children of God (Rom. 8:21). “Are not two sparrows sold for a farthing? And one of them shall not fall on the ground without your Father. But the very hairs of your head are all numbered. Fear ye not therefore, ye are of more value than many sparrows” (Matt. 10:29-31). We do well to remember more often the cosmic scope of God's covenant, that it embraces the four corners of the earth and every living creature therein, and reaches out to the farthest bounds of the universe, to the astonishingly vast galaxies with their billions of stars and all the hosts of the highest heaven. For Christ, God’s own Son, shed his blood to reconcile all things to God and bring them into his covenant (Col. 1:20).

God set the rainbow in the clouds as a wonderful token of this covenant with all creation. As a man puts a diamond ring on the finger of the woman he loves when he enters into the covenant of marriage with her, so also the Lord put that magnificent arc of colors in the sky as a sign of his everlasting faithfulness and abiding love for his creation, in which his people in Christ are to him the most precious of all. God bring the day when we will stand before him with all creatures and sing, “holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts. The whole earth is full of his glory” (Is. 6:3, Rev. 4:8).

_______

Featured book:

The content of the article above is the sole responsibility of the article author. This article does not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of the Reformed Free Publishing staff or Association, and the article author does not speak for the RFPA.

Donate

Your contributions make it possible for us to reach Christians in more markets and more lands around the world than ever before.

Select Frequency

Enter Amount